“The students that go on to succeed work really hard, love collaborating and aim high.” Each month, we’re catching up with one of NIDA’s creative leaders, to show you the artist behind the educator. This month we sat down with Dr Julie Lynch, the Director of the Centre for Design Practices.

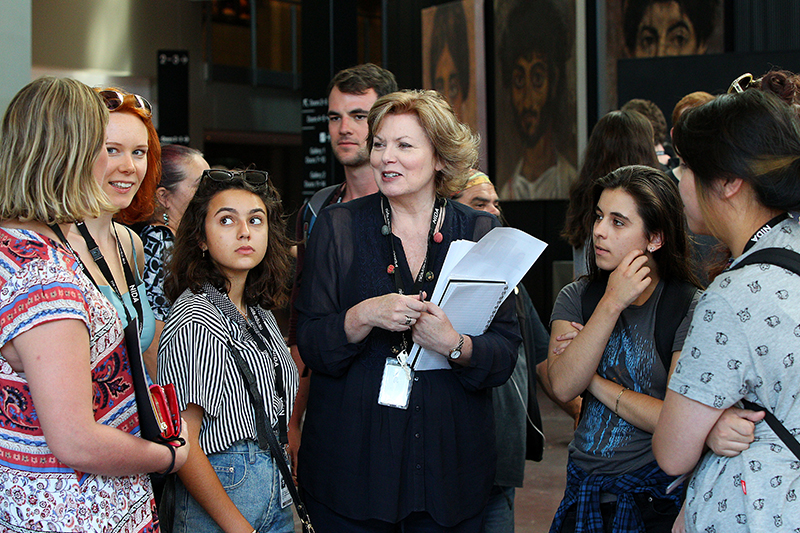

Dr Julie Lynch with students at NIDA’s Welcome Week, 2018

Each month, we’re catching up with one of NIDA’s creative leaders, to show you the artist behind the educator. This month we sat down with Dr Julie Lynch, who was formerly NIDA’s Head of Design. In the new phase of NIDA’s conservatoire model, with disciplines focused around creative centres, Julie is Director of the Centre for Design Practices.

Who and what comes under the Centre for Design Practices?

The Centre for Design Practices houses all of the design and making courses. These are comprised of the pure design course, Design for Performance, and the ‘design and making’ courses, which are Costume; Properties and Objects; and Scenic Construction and Technologies. Bringing these into the one centre means we can share resources, knowledge and expertise in a more significant way.

These disciplines naturally work together. In NIDA’s production season, the Design for Performance students design the shows; they create the ideas with directors and performers, then the Costume, Properties and Objects, and Scenic Construction and Technologies students realise the work.

How has NIDA’s world of design changed from the 1970s through to today?

In the history of NIDA, the design course ran for almost 20 years before the specialist sets, props and costumes courses were introduced. This meant that in the 1970s and ’80s, the design students used to make and build everything themselves.

Dr Julie Lynch as a NIDA Design student, 1984

As we went into the ’90s, the specialist courses were created, allowing more sophisticated, complex, and better realised designs on stage, because we were now collaborating with students who specialised in learning how to make.

In this century, we’ve seen how technology can support design and making in a very sophisticated way. In the Centre for Design Practices, we can digitally cut and print objects, we can scan three-dimensional objects and then build them, we have 3D printing, shapes that can be automatically cut out on CNC machines, we have a MAC studio and a CAD studio where students learn to work on a wide variety of design software. These tools and techniques didn’t exist at NIDA last century. Everything was far more analogue.

We still embrace analogue, but we supplement and enhance our analogue work through digital means to generate more work faster, and we can experiment and explore all aspects of realisation using a wide range of materials and techniques.

First-year Lucas Guillemin with a 3D-printed replica of a 1980s telephone

What did you love about NIDA as a student, and what do you love about NIDA now?

When I studied here in the early 1980s, NIDA had very limited facilities, but it still had the kind of creative energy that it has now – you’re in amongst a group of like-minded creative people. That was my time, with a whole group of students who I’ve remained friends with – not even necessarily from my own course. They’re people I’ve worked with time and time again outside NIDA.

People like Mel Gibson, Judy Davis, Baz Luhrmann and Stephen Curtis had gone on before me. There were great people coming out of NIDA and making their mark very quickly, so we all knew that it was a very special place. It’s the same kind of people coming together to study at NIDA today – with the same amount of creative energy – but it’s their generation now.

With NIDA’s expanded offering of courses, we now have a larger group of students, but they’re still similar – resilient, incredibly tenacious and creative. In my opinion, the students that go on to succeed are the ones that are not only talented but love what they do every day. They’re curious, creative artists that work really hard, love collaborating and aim high.

That was happening in the ’80s when I was a student and it’s still happening now. They bring their personality, ingenuity and individuality to whatever they do, no matter which course they’re studying.

A moment from 2018 NIDA production, the Chekhov-inspired Ah Tuzenbach, A Melancholic Cabaret featuring second-year acting students

How is design changing in the wider world?

We’re working in a more expanded environment. In the ’80s the opportunities were theatre, film and television; there was no such thing as interactive theatre, games, websites or any of the digital platforms that now provide opportunities for working in performance.

The director of UCLA’s costume design degree, Deborah Nadoolman Landis, claims that in the USA, there’s more employment for costume designers in games than in films. That’s an American scenario, but I think it will become bigger here as well.

Design is more prevalent everywhere now. There are more events where people have high expectations about how things should look, which means our designers work in a wide variety of fields.

How did you enter the world of design?

After leaving school I trained in graphic design. I spent a year working in advertising and it wasn’t the world for me. I’d heard about NIDA and I thought, ‘That sounds interesting. I’ll give it a go.’ I hadn’t been much of a theatre-goer, but I loved movies, and I was accepted to NIDA.

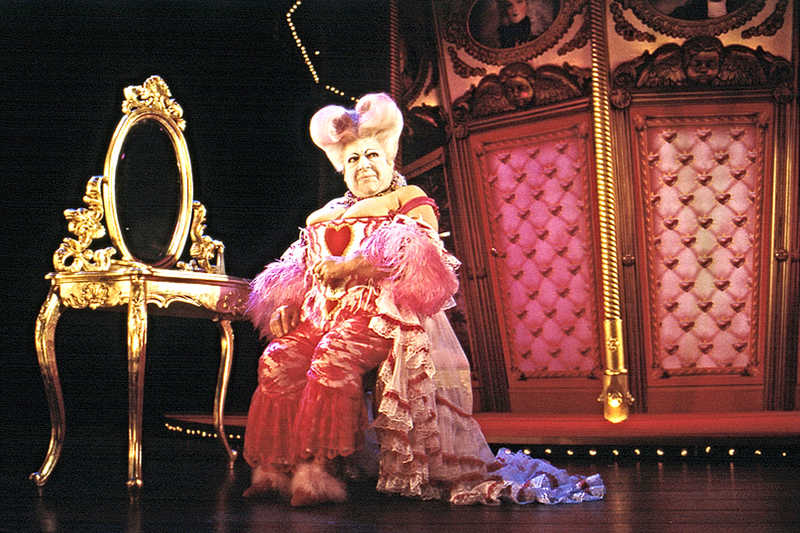

Sydney Theatre Company’s 2014 production of Noises Off, for which Julie Lynch won Best Costume Design at the Sydney Theatre Awards

What was your first big break into the industry?

In the 1980s, when I was at NIDA, the Head of Design at that time, Robin Lovejoy, would organise a work placement for all the students at the State Theatre Company of South Australia. My placement must have gone well because I was offered a permanent role as a junior resident designer.

This was one of my first jobs. It was fantastic because it was such a well-resourced company. They had a soft props store – soft cushions and soft sculptural things; and a hard props store where they made furniture; they had a wig department, a millinery department and a scenic art department. You’d be hard-pressed to find that now.

It was a fantastic training ground (even though I thought I knew everything). I got to work in different theatre spaces designing sets, props and costumes, and I also worked as an assistant to some very experienced, significant designers who came to the State Theatre Company on larger shows.

Sydney Theatre Company’s 2003 production of The Way of the World, for which Julie Lynch won the Helpmann Award for Best Costume Design

One of the designers I worked for during that time, Brian Thomson AM, went on to engage me as a design assistant on some very large musicals, including The King and I, which went over to New York and won a Tony Award. I now employ Brian to come in and teach the design students.

These jobs continually connect you to industry. I didn’t have any definite pathway. As creative practitioners, we take a leap of faith on an opportunity and we see what it turns into.

Where do you personally go for ideas and inspiration?

I think you have to be curious as a designer. You have to mix up where you seek inspiration. If you’re really immersed in the development of a new show or design, your mind never stops being open to what’s around you. The projects don’t leave you.

Yes, you might go to galleries and libraries, but you could just be on the bus and you’ll see a character across the aisle that you’ll take inspiration from.

Inspiration is everywhere. It’s all around you. It’s up to you to pick it up and do something with it. That’s what’s important.

Dr Julie Lynch at the University of Sydney with her Doctoral Supervisor Dr Glen McGillivray, 6 November 2018

Earlier this month, Julie received her doctorate from the University of Sydney. Her thesis, Costume’s Mirror up to Nature, examined the contribution that costume design makes to scenography, interrogating the traditional hierarchy of set design over costume, and revealing how costume design has been traditionally ‘feminised’ through education and employment practices.

If you are interested in any of the design or making courses offered through the Centre for Design Practices, view Undergraduate offerings here or Postgraduate offerings here.

Applications for 2019 courses are now closed. For late application requests, please contact the Learning and Teaching Team at applications@nida.edu.au as soon as possible.